Clarity and Aesthetics in Visualization: Attention, Contrast, Grouping

Three concepts from visual perception that can help you think better about clarity and aesthetics

In my previous post I introduced a series of guidelines on clarity and aesthetics. Here I’ll try to expand on these guidelines by providing a more generalizable perspective based on notions of visual perception. I find that while showing examples and giving guidelines is crucial to improve practice, even more important is to help students think about these idea in a more abstract and generalizable manner. As an instructor, I can’t anticipate all the possible situations where detrimental effects of clarity and aesthetics will show up, but I can help students think more clearly about the principles and the basic mechanisms of human vision that can guide their thinking. Note, that this is definitely not a full account of what happens at a perceptual level and I am definitely not an expert in in this area. This is more the way I like to think about these problems based on the few notions of visual perception I have acquired over time.

Attention

Attention is a little hard to understand at first. Especially, if you’ve never introspected on how your mind works. But the thing is, when we are shown a visualization our eyes try to make sense of it. “How do I read this? What does it mean? Where is the information I am looking for? What is the information I am supposed to extract from this?” Etc. As we do this, our eyes scan the visualization and focus on different areas and elements. One way Colin Ware describes this is that attention is about “tuning”: we tune our attention to specific elements and aspects of the visual representation so that we can draw information out of it.

Why is this relevant here?

It’s relevant because clutter (spurious elements) divert attention to elements of the visualization that are not functional to the goals of the visualization. One way to think about it is that these elements “compete” for attention: they tell you to focus on them when you should rather focus on something else. Think about the elements I mentioned in my previous post: grid lines, borders, labels. They all compete for your attention to the detriment of other elements that show the patterns in the data.

Attention is such a key concept in visualization. Once you start thinking about how your attention is modulated by your design, you have a much richer understanding of what is going on and where some problems may emerge.

Contrast

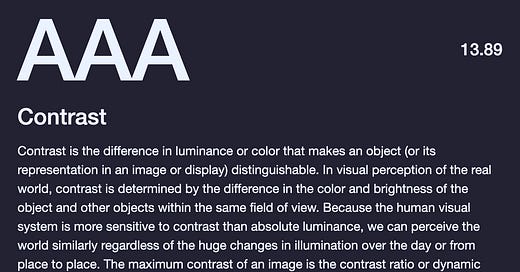

Contrast is another difficult concept to define and grasp at first. What is contrast? Contrast is the difference between colors and brightness of the visual elements that are present in your visualization. Brightness is especially powerful in this sense. If you have a very dark object near a very bright one, you have a lot of “contrast” between these objects. If you instead have objects of similar brightness next to each other, they have a very low contrast.

A useful way to grasp this concept is to play with a “contrast checker”. There are many online if you google it. Here is a simple one that I like.

The key when thinking about contrast is to think about differences and abrupt changes. Think again about heavy gridlines, borders and labels. They all have a lot of contrast concentrated in very small areas. See the difference between the one on the left and the one on the right.

Keep in mind that this does not mean that low contrast is always good and high contrast is always bad. In fact, if you look at the example below (similar to the one I discussed in the article on guidelines) you will see that if your visual marks do not have enough contrast with the background, they will just fade away. Yellow dots on a white background is such a classic problem I see in class all the time.

In visualization you can typically bump into three main problems with contrast:

Contrast between the visual objects that depict the data (Are there objects that stand out? Is that a goal of your design or an hindrance?);

Contrast between the visual objects and the background (Do the objects stand out from the background? Are they actually visible?);

Contrast between the visual objects, peripheral elements such as grids, borders, labels, and the background (Do the peripheral objects help or intrude? Do they attract excessive attention?).

All of these need to be coordinated so that their combination works in a beautiful synergy.

Grouping Effects

Our visual system has a number of interesting ways to perceive visual objects as being part of a “group”, that is, the way they look leads us to perceive them as being somehow grouped. The classic example is a set of random dots vs. a set of adjacent dots. The ways dots are positioned suggests grouping.

This is what is normally described in the “Gestalt laws of grouping”. I don’t want to go through all of them here. If you are not familiar with the concept follow the link above. But the main idea here is that the way you space and align visual objects in your visualization suggests grouping and, in turn, grouping suggests a direction for reading. So, when we talk about spacing and sizing above, the main principle to keep in mind is that the visual system tends to group objects together according to how they are aligned and spaced, and in turn this suggests a reading direction. The classic example is the one you see below.

This is the same set of objects arranged in a grid. The only difference is the amount of space between the columns and the rows. More space between the rows and you see column. More space between the columns and you see rows.

Summary

As an extrapolation of the guidelines I presented before, I’ve proposed three main concepts that are common in visual perception: attention, contrast and grouping. I find it useful to think about these concepts when evaluating a visualization.

How is attention “modulated” by the elements of the visualization? Is there anything that attracts attention too much? Conversely, are there elements that should be more separated visually? Maybe some of the objects with respect to the background? High contrast is a super powerful way to attract attention so detecting areas of high contrast can be useful. Similarly, detecting problems with too low contrast can also be useful. Finally, grouping effects are everywhere. Being mindful of how they impact reading direction and pattern formation is a very useful skill.