Titles in Data Visualization: Empirical Evidence

Two studies that shed a light on the key role of titles in visualization

While preparing for a new class in my Rhetorical Data Visualization course, I stumbled upon several interesting papers on using titles in data visualization. However, data visualization resources are surprisingly devoid of information about titles, and the few ones I found tend to be quite superficial.

Titles are interesting because they do not really “encode” data graphically, so they receive comparatively little attention. In line with my initial intent of going beyond visual representation in my courses, I have embarked on having a strong module (and corresponding exercises) on using titles. In this first post on titles, I’ll cover interesting results I gathered from scientific studies. In my next posts, I’ll cover more practical ideas on designing and thinking about titles.

In covering the science of titles, I’ll focus on results gathered from the following two papers:

Borkin, M. A., Bylinskii, Z., Kim, N. W., Bainbridge, C. M., Yeh, C. S., Borkin, D., Pfister, H., & Oliva, A. (2016). Beyond Memorability: Visualization Recognition and Recall. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 22(1), 519–528.

Kong, H.-K., Liu, Z., & Karahalios, K. (2018). Frames and Slants in Titles of Visualizations on Controversial Topics. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12.

Let’s first review some of the main elements of the studies presented in these papers.

In Borkin et al., the subjects went through three main steps. First, they showed them a set of visualizations, each for 10 seconds, and tracked where they looked using eye-tracking. Second, they showed a subset of the visualizations they saw, mixed with new visualizations they had not seen, and asked the participants to recognize the ones they saw in the previous steps. Finally, in the third step, they showed some of the visualizations they inspected in step one but blurred and asked them to recall their content. While the study is about memorability, as you will see below, the results provide several insights into the role of titles. The image below summarizes these steps as presented in the paper.

In Kong et al., the subjects were exposed to two separate visualizations covering controversial topics: refugees and military spending. To study the effect of titles, they exposed the participants to different titles, one supporting and one not supporting a given policy. The visualizations were cleverly designed so that readers could derive opposite conclusions according to which elements of the charts they focused on so that both titles could go with the same visualization. The image below shows the visualization used for the Syrian refugee policy, with the two titles they used.

After exposing the readers to these visualizations, they asked them to recall the central message of the visualization (to verify the effects of titles) and then whether they perceived any bias in the visualization.

Now, let’s turn to the main findings of these two experiments and see what we can learn from them.

1. Titles attract a lot of attention

The first thing we can learn from existing research is that titles are the most prominent visual object readers focus on when exposed to a new visualization. In the Borkin et al. study, readers spent most of their time fixating their eyes on titles. You can see this effect in the image below. The top part with text is often the one that receives the highest number of fixations. These are the brightest parts on the heat maps.

Interestingly, they found that table headers were fixated more often than titles when titles were at the bottom of a table. So, one conjecture we can make is that the power of titles resides in two properties: the textual representation they use and their position on the page/screen.

2. Titles is what people memorize

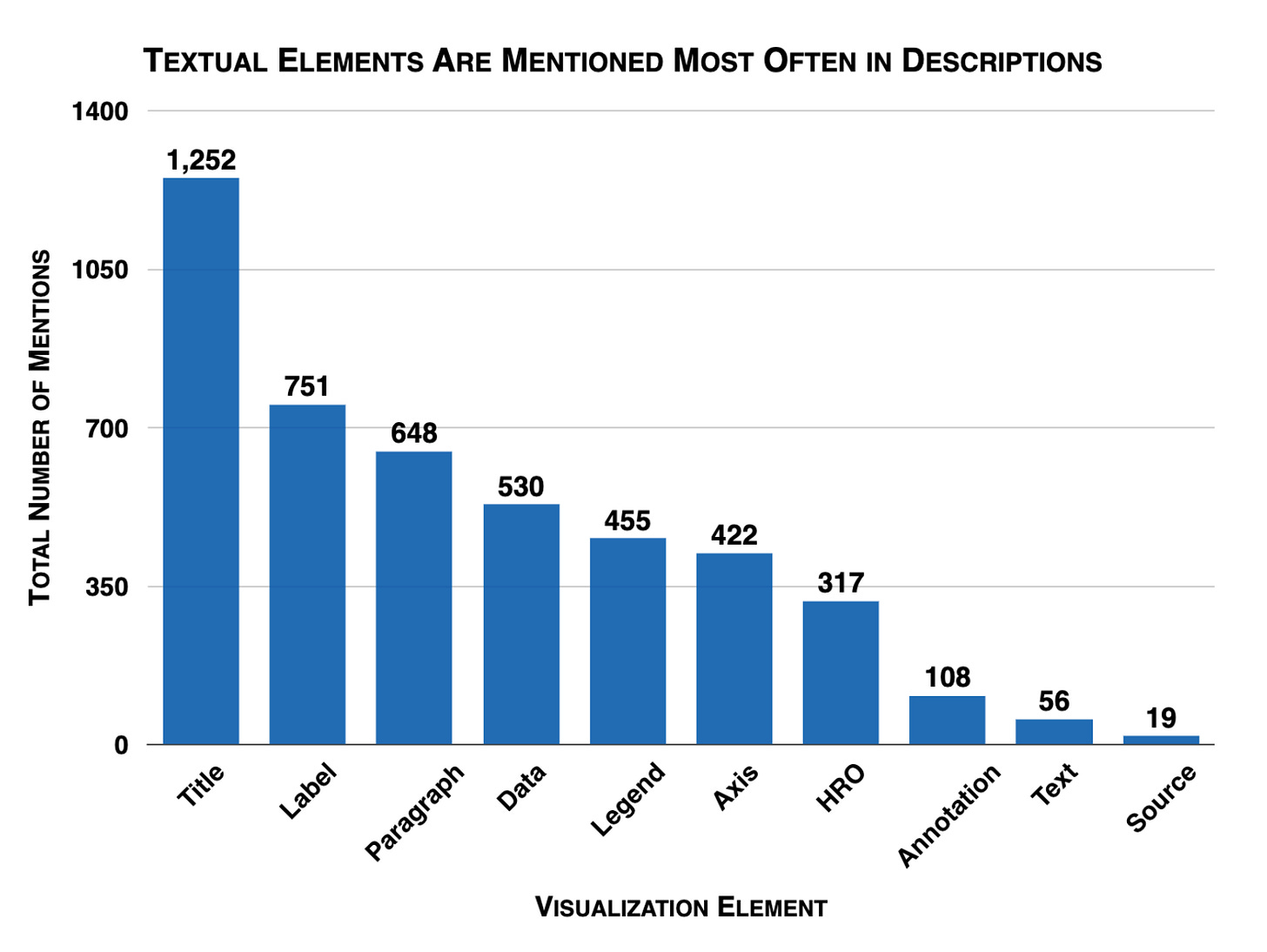

When asked to recall the content of a visualization, the participants in the Borkin et al. study mentioned titles the most. The chart below summarizes how often different types of objects were mentioned in the recall phase (interestingly, most other objects are textual objects).

The authors also scored the descriptions based on their quality and found that visualizations containing titles were of higher quality. Not only do people memorize titles the most, but when titles are not present, they have a harder time describing the content of a visualization.

3. Titles influence recalled messages

When asked to recall the main message of the visualization, the participants in Kong et al. mentioned a message that was more often aligned with the content of the titles. The table below summarizes the results.

Surprisingly, these results did not depend on the participants' attitudes toward the policy advocated in the chart. The authors collected this information and found that previous attitudes did not have an effect.

Borkin et al. found a similar result regarding what is recalled from a visualization as the main message. When titles contained the visualization's main message, they could easily recall it, but when the titles were more generic, fewer people recalled the main visualization’s main message.

4. Slants/bias in titles can go unnoticed

An even more surprising result of the study by Kong et al. is that the readers did not find the visualization biased at all. As you can see in the chart below, the large majority of the participants considered the visualization neutral, and the results did not depend on whether the policy advocated was consistent with the readers' attitude.

Follow-up work from Kong et al. found that the slant is often unrecognizable even when titles present something that completely contradicts the visualization’s content. I will try to describe that study in more detail in a future post. In any case, as you can see, titles have a pretty big impact!

Implications

From these observations, we can conclude that titles are fundamental to data visualization. I’d say, “Ignore them at your peril!” We also saw that titles have a huge impact on how people interpret a visualization and what information they extract from it. A consequence is that titles are almost too powerful, and we must use them with great care. As we will discuss in a future post, visualization designers (and scientists!) often feel like they have to stay away from biasing the reader, and because of that, they avoid titles that guide the reader too much. But this comes at the cost of limiting the positive effect of titles in aiding readers in interpreting a visualization correctly. In the next post, I will start looking into this issue more closely.

—

If you enjoyed this post, please help me share it with as many people as possible. You can like it, leave a comment below, post it on social media, email it to your colleagues or friends, etc. If you are not a subscriber of FILWD yet, I encourage you to subscribe. You will receive updates about this kind of ideas directly in your inbox on a weekly basis.

Thanks,

Enrico.

Fascinating! Cant wait to read the rest.

Just to add a bit of information, this is from a 1914 book on charts: https://archive.org/details/graphicmethodsfo00brinrich/page/344/mode/2up